The Stories That Shaped My Curiosity in PR

Before I ever took a PR class, I was already paying attention to how people, brands, and moments were portrayed in the media, even if I didn’t realize it at the time. I’ve always been fascinated by the space between what happened and how it’s being talked about. What gets left out? Who controls the narrative? And why do some people walk away with their reputations intact while others never recover?

These stories, some cultural, some personal, some fictional, stuck with me. They each showed me a different side of public relations: how it can inspire, manipulate, protect, or completely fail someone. From the myth of JFK’s Camelot to the fallout of Nipplegate, from Olivia Pope’s command of a crisis to the uncomfortable branding of early Britney Spears, these were the moments that made me stop and think, ‘Who’s running this? And how would I handle it differently?’

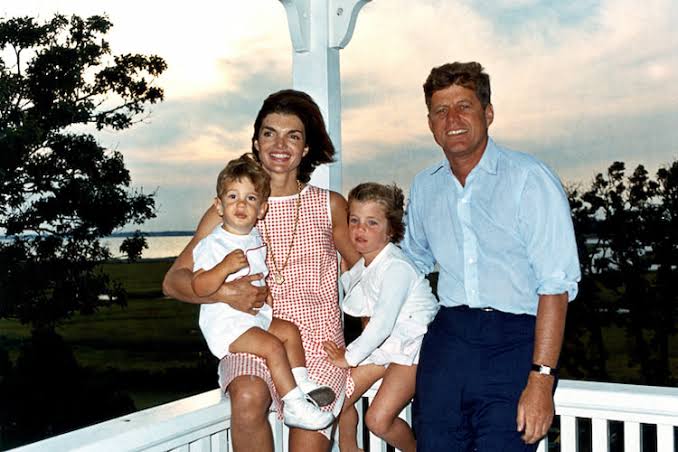

JFK’s Camelot

I remember first learning about President John F. Kennedy and being struck by how much his image shaped his rise to presidency. It wasn’t just about policy, it was the way he and his family were portrayed: young, polished, full of hope. The Kennedys looked like the American dream in motion, with their glamour, charm, and carefully curated public life. After his assassination, Jacqueline Kennedy gave an interview where she compared his presidency to Camelot– a golden, idealistic time that would never come again. That single reference reframed JFK’s legacy, turning it into a mythic era of hope and possibility. It was intentional, emotional, and incredibly effective.

What fascinated me was how storytelling could carry that much weight. The public’s connection to JFK wasn’t just about what he did, it was about what he represented, and how powerfully that image was reinforced by the media. When he died, it felt like the country lost more than a leader; it lost the narrative of hope that had been built around him. That kind of emotional impact, created largely through PR and framing, made me realize how powerful narrative can be. It’s what first pulled me toward PR — the idea that how a story is told can shape how people feel, remember, and respond.

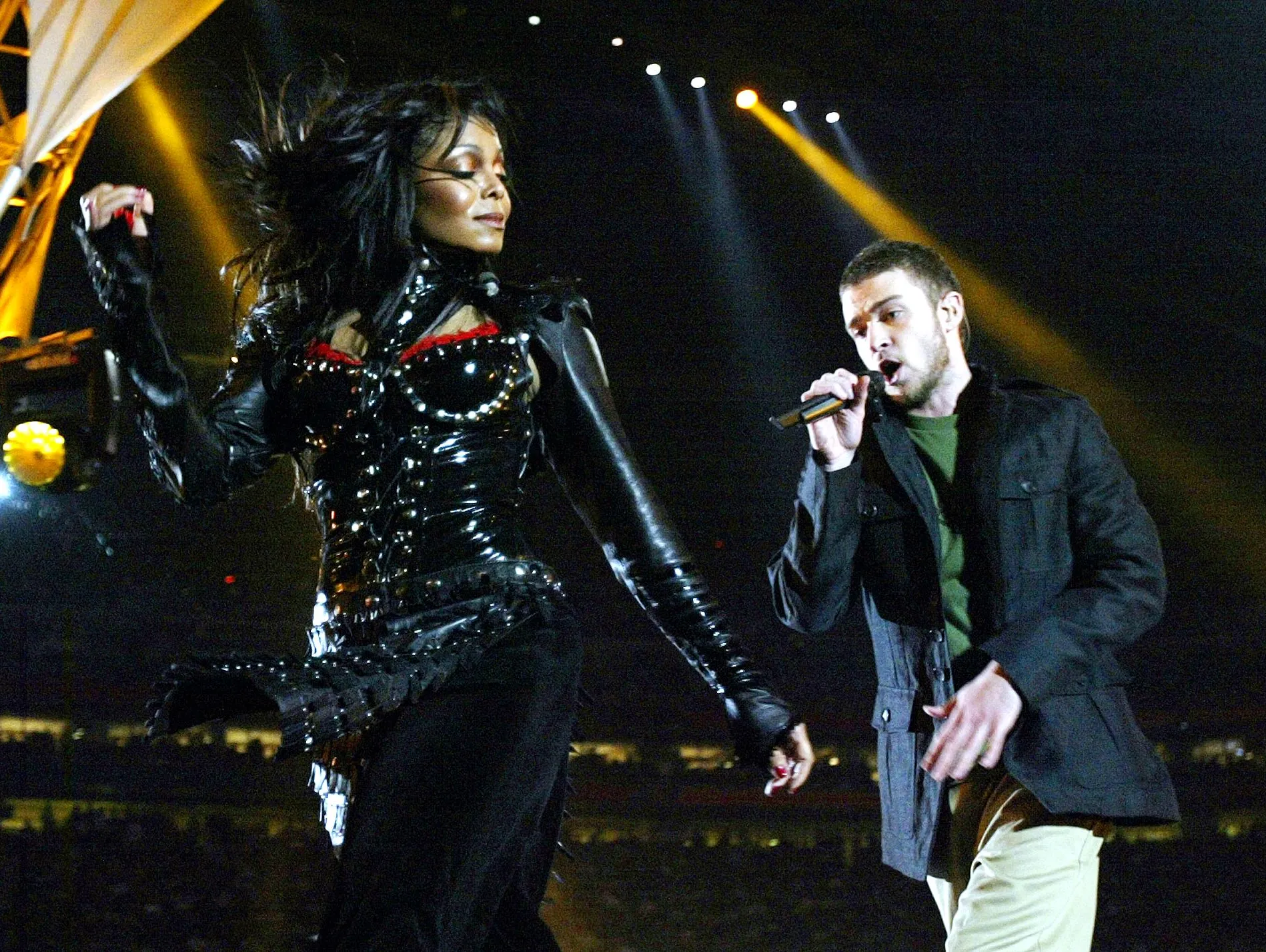

Nipplegate: The Power and Pitfalls of a PR Response

I was very young during the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show, but I remember watching the performance live. I didn’t even realize Janet Jackson’s breast had been exposed, it happened so fast. It was the media that turned it into something massive. They slowed it down, replayed it, dissected it, and magnified it into a national scandal. That moment, now known as “Nipplegate,” became one of the biggest PR controversies in pop culture history and the fallout to follow was intense.

What really stayed with me was how uneven the response was. Janet Jackson faced immediate and severe consequences. She was blacklisted from major networks, disinvited from the Grammys, and watched her career momentum completely stall. Justin Timberlake, meanwhile, managed to distance himself from the incident, even coining the now-famous phrase “wardrobe malfunction.” In the years since, public attention has started shifting toward Timberlake’s role in the aftermath, but to me, the deeper issue was always about the lack of protection and direction Janet received. The people who made the decision to erase her from the airwaves, the media execs, corporate gatekeepers, and industry figures walked away untouched.

In her Lifetime/A&E documentary, Jackson defends Timberlake and confirms she told him not to say anything publicly. It’s been rumored she wasn’t happy with how her own team handled the crisis overall and I couldn’t agree more. There was no unified strategy, no proactive messaging, no framing of her side of the story. She was left to carry the entire weight of the controversy alone.

I’ve always wished I could have been in the room during that moment, not to “fix” the crisis itself, but to manage the response in a way that was fair, strategic, and protective. This situation taught me that PR isn’t just about headlines, it’s about who gets heard first, who gets shielded, and who gets thrown under the bus. This moment made me realize I want to be in PR not to clean up the mess after it’s already taken a life of its own, but to help shape the narrative early on with intention, fairness, and clarity before it turns into a disaster.

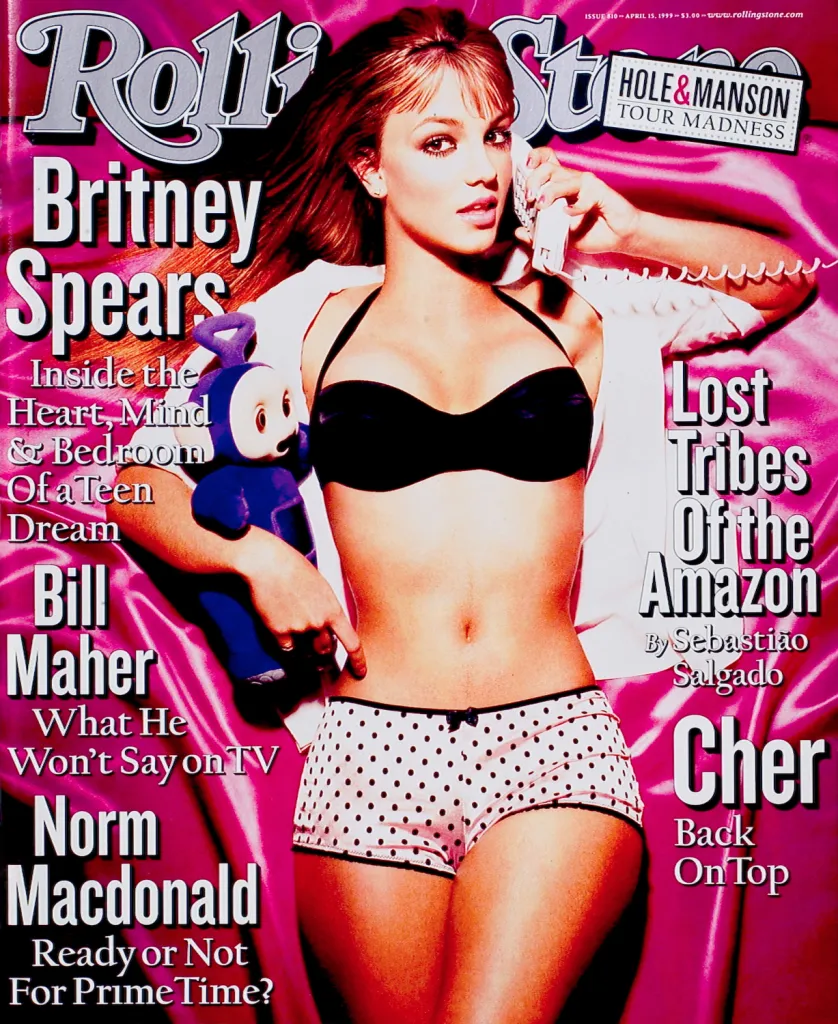

The Marketing of Early Britney Spears

What fascinates me most about early Britney Spears isn’t just how she was marketed but how much people bought into it. She was framed as this sweet, all-American teenager, yet styled and positioned in ways that were overtly sexual. That tension between innocence and provocation was the brand, and the media pushed it hard. The obsession with her virginity, the inappropriate interview questions, the way the public consumed it all like entertainment. Looking back, it was rooted in misogyny and pedophilia, packaged as pop culture. And it worked, because no one questioned it. That’s what really grabbed me: not just what was done to her, but how PR and media made it feel normal.

She had almost no control over how she was portrayed, even though she was the face of a billion-dollar machine. And when the narrative turned on her, the same media that built her up was first in line to tear her down. That made me realize how much power there is in the way stories are told and how dangerous it is when that power isn’t used responsibly. Britney’s story didn’t just make me interested in PR; it made me want to do it better. To think critically, to protect people, and to help shape narratives with intention before they spiral. Because if we don’t question why certain stories work so well, we’ll just keep telling the wrong ones.

Olivia Pope on Scandal

I know Scandal is fictional, but Olivia Pope was the first time I saw a PR professional portrayed as the ultimate fixer. She wasn’t behind the scenes, she was the scene. She handled crisis after crisis with confidence, strategy, and urgency. Whether she was coaching a client before a press conference or cleaning up a political scandal before it broke, she made PR feel intense, impactful, and necessary. Watching her operate made me see that PR isn’t just about writing statements, it’s about knowing how to act when no one else does.

Of course, the drama was exaggerated, but the fundamentals were real. Olivia showed that reputation is everything, and that in high-stakes moments, how you respond is just as important as what actually happened. She was calculated, intuitive, and didn’t let emotions get in the way of the bigger picture, and even though it was TV, it resonated with me. It made me curious about how these moments play out in real life, and it’s part of what pushed me toward crisis PR. I don’t need to wear the white coat, but I do want to be the person behind the strategy when it matters most.